Do We Stand At The Precipice Of Radical Change

“Just on the border of your waking mind/ There lies another time/ Where darkness and light are one” — E.L.O.

If unrest in America has peaked, you wouldn’t know it from people’s tweets. World War 3, civil war, and apocalyptic climate change are the standard topics of discussion now. Saying that “democracy is dying” and members of the opposite party “literally want to kill you” is de rigueur when discussing electoral politics. On Signal, friends ask me in hushed tones whether they should stockpile food or move out of the country.

Perhaps no tweet so perfectly sums up the vibe on social media as this one:

Quoting Rosa Luxemburg, Potash goes on to declare that it’s “socialism or barbarism”.

It’s understandable that Americans would feel this way right now. We’re in the middle of a pandemic that has probably killed a million of our people and is still killing thousands a day. A year and a half ago we had the largest protests the country has ever seen, and a year ago we had what was arguably our country’s first real coup attempt. Violent crime is high and rising, with every day bringing lurid reports of new atrocities. Russia is on the verge of invading Ukraine, while China menaces Taiwan, India, and Japan. And over it all looms the menacing shadow of climate change, as wildfires, hurricanes, and extreme heat events become commonplace.

At such a time, it’s reasonable to deal with the darkness of the present by reaching for radical hope. For many young people, this means some flavor of socialism — a pastoralist degrowth that will stop the runaway train of progress, or a futuristic “luxury space communism” that will solve climate change while delivering techno-prosperity for all. This utopianism reminds me of the character Lauren Olamina in the novel Parable of the Sower, who deals with the trauma of her collapsing society by declaring that humanity must spread throughout the stars.

“Socialism or barbarism” — is it so crazy to think this is the choice we face? In the 20th century we had both. William Butler Yeats wrote “The Second Coming” in 1919, and his words proved more prophecy than hysteria. In the decades that followed, Yeats’ “rough beast” was indeed born — the global economy collapsed, a world war claimed 60 million lives, and ideological nightmare regimes sprung up and killed tens of millions more (often in the name of socialism!). And yet during those decades we also saw the social-democratic West achieve heights of prosperity and freedom hitherto unimagined, while inequality and poverty plummeted; meanwhile, the world freed itself from the yoke of European colonialism. It was an age when grandiose fantasies and grotesque nightmares came true.

So it’s not impossible that we stand at a similar precipice now, a century later. But it’s also worth remembering a very different time, when it also seemed to many that the world stood on the edge of disaster, but we ended up muddling through. That would be the late 20th century.

1965-1994 was crazy, but we muddled through

“And as you tread the halls of sanity/ You feel so glad to be/ Unable to go beyond” — E.L.O.

Most Americans are now too young to remember, but in the early 1970s domestic terrorist attacks became so commonplace that they were practically ignored — over a year and a half during 1971 and 1972, the FBI counted over 2500 bombings in the U.S. Most of these attacks didn’t kill anyone — they were just bombs that blew up empty buildings. But imagine the hysteria if this was happening multiple times a day in 2022! Two left-wing radicals tried to kill President Gerald Ford within a three-week period in 1976!

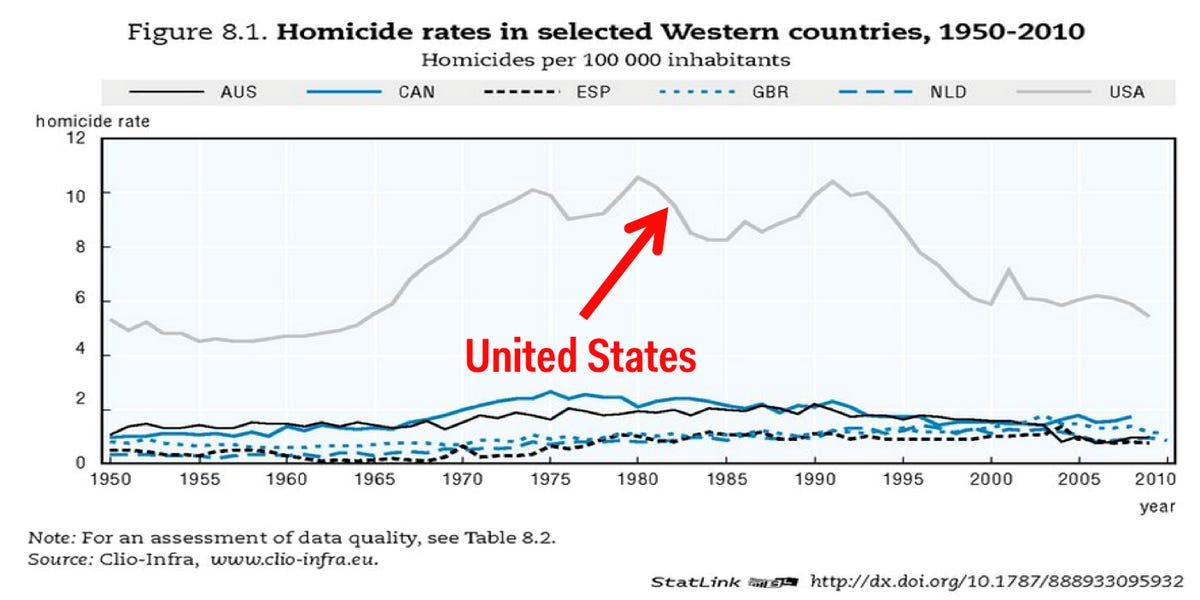

And people were dying. In the late 60s and 70s, the murder rate — always much higher in the U.S. than in other rich countries — spiked to levels not seen since the 19th century, and stayed high until the late 90s:

In cities, the rates were far higher. Horrifying violence became commonplace — when Madonna moved to New York City in 1977 at the age of 19, she was raped at knifepoint on the roof of a building, mugged at gunpoint, and had her home broken into three times. In 1990, NYC saw 2,262 murders.

And a substantial amount of this violence was racially or religiously motivated. In the late 1980s, hate crime referrals to the FBI were almost 10 times as high as in the late 2010s. Data aren’t available before that.

Protests and riots were a fact of life during these years as well. The late 60s and early 70s didn’t see any single week of protesting as intense as the first two weeks of the George Floyd protests, but the nationwide protest campaign against the Vietnam War went on far longer and almost certainly ultimately involved many more person-hours. The riots of the late 60s and early 70s resulted in far more deaths than the Floyd protests; even the single-city riot in L.A. in 1992 killed far more than all of the Floyd protests combined. (Let’s not forget that George H.W. Bush sent the U.S. Marines to suppress the L.A. riots — something Trump never managed to convince his generals to agree to in 2020.)

Even the 1990s, which we now remember as a time of social tranquility, were pretty wild. Parable of the Sower came out in 1993! It was 1994 when a right-wing terrorist blew up a building and killed more people than any other terrorist attack on U.S. soil other than 9/11. Just an hour down the road from where I grew up, the FBI and the ATF put a cult under siege, and 86 people ended up dying. In 1996, the Atlanta Olympics that was supposed to symbolize the post-Cold War triumph of peace and democracy was bombed by a right-wing terrorist.

The three decades from the mid-60s to the mid-90s were, simply put, a time of violence and madness. And let’s not forget the economic catastrophe of the late 70s stagflation, the wage stagnation between roughly 1973 and 1993, or the double-digit unemployment rates of the early 80s.

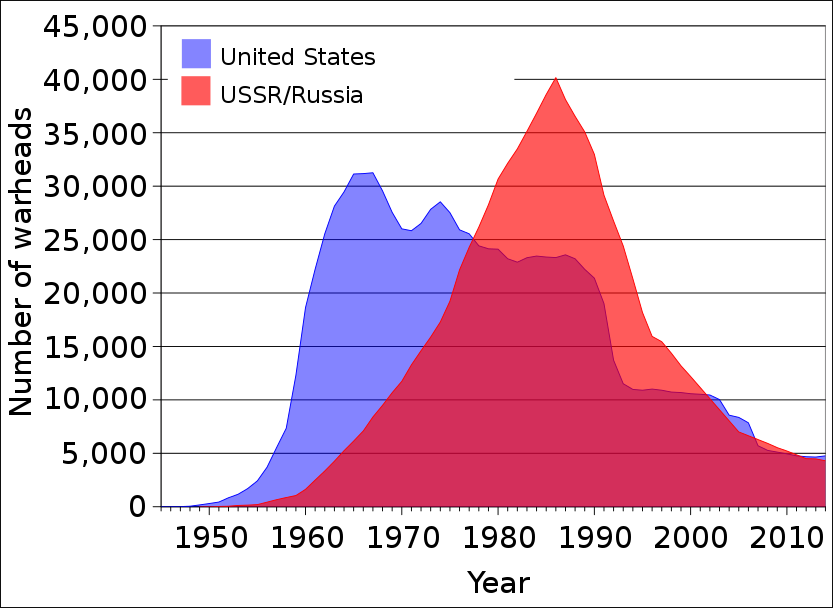

And as for looming catastrophes, eco-dystopias were already starting to appear in the 70s, but the true Sword of Damocles was nuclear war. Tens of thousands of Soviet tanks stood ready to roll into the Fulda Gap at any moment. By the late 80s, the U.S. and USSR were facing each other with over 60,000 nuclear weapons, many on hair-trigger alert.

If not for the quick thinking of the stalwart Stanislav Petrov, human civilization might have been immolated in 1983 due to a computer glitch. And that was just something everyone lived with, every day. Until the USSR fell in 1991, I simply assumed that at some point the world would be nuked, and that we were all living on borrowed time.

And yet in the end, what happened? Armageddon didn’t happen. There was no global socialist revolution or fascist reaction; instead, most countries just liberalized and democratized in the 80s and 90s. Milquetoast neoliberalism became the dominant philosophy of how to organize a society. Terrorist attacks guttered to a low background hum, as did riots and violent crime. By the turn of the millennium, the idea of overthrowing the U.S. government seemed like a joke.

In other words, we muddled through. Life puttered along. The horrors of the early 20th century saw a few echoes in the late part of the century (Cambodia’s killing fields, China’s Cultural Revolution), but overall, the nightmares of the earlier decades were remembered and were not repeated. Americans generally remember the 70s as a time of social and political exhaustion, the 80s as a time of silliness and consumerist distractions, and the 90s as a golden age.

So while it’s possible that the 21st century might repeat or even exceed the horrors and wonders of 100 years ago, it’s equally possible that things might putter along like they did 50 years ago.

BUT, say the people who cry “socialism or barbarism”. BUT. Now, unlike in the 80s and 90s, climate change is finally beginning to bite. And this changes everything, because even if racial and partisan unrest fade, and World War 3 never materializes, ecological disaster means that muddling through is no longer an option.

Does climate change change everything?

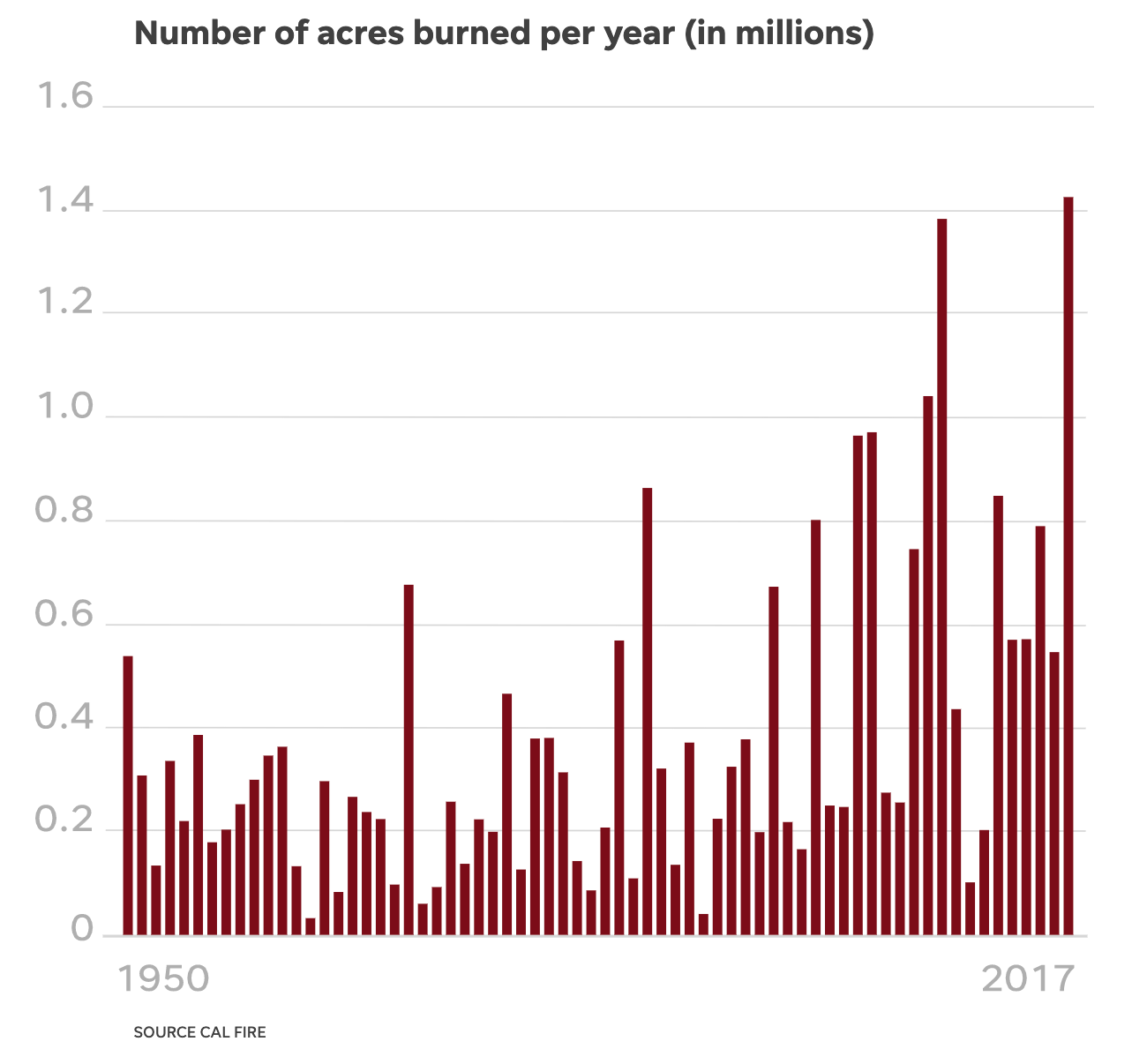

The people who still deny either the existence, the cause, or the importance of climate change are divorced from reality. This thing isn’t coming; it’s here, now. Anyone who now trembles at the return of the annual “fire season” in the former paradise known as California understands both the imminence of the threat, and how it can manifest in unexpected ways:

(If you’re still in doubt as to climate change’s contribution to this trend, read this post by Jose Luis Ricon.)

Of course, it’s not just wildfires in California. It’s heat domes in Portland and Seattle. It’s eroding home values on the East Coast. It’s increased flooding along rivers and crop destruction in the Northeast and Midwest. It’s intensified hurricanes along the Gulf Coast and drought in the Southwest and in the Plains and Upper Midwest. And this is just the beginning.

What’s more, the world has probably now passed the point where concerted action could prevent major impacts from climate change. Holding the world to the 1.5ºC widely touted as the level necessary to prevent major global impact now seems like an impossible goal, as it would require immediate and drastic changes to the world economy over the next two decades.

Even if the U.S. were willing to enact the full Green New Deal (which we are not), and even if this successfully dropped our own emissions to near zero (which it would not), this would only represent a modest fraction of the global total; China and other Asian countries, which together now represent the majority of global emissions, are still building new coal plants at a fairly rapid clip.

To socialists, this really changes everything as far as global governance and the organization of society are concerned. Incrementalism has failed, and the only chance at stopping global catastrophe is the radical recreation of human economies and societies along socialist lines. Just what this would look like — a pastoralist future of degrowth, the “fully automated luxury communism” of the Green New Dealers, or something more authoritarian, is a topic of hot debate on the Left. But nowhere is the option of muddling through given serious consideration — one way or another, it’s asserted, climate change will demolish the society we live in now.

And yet to me, it seems easily possible to imagine a future where we don’t just muddle along with business-as-usual, but in which we do address the threat of climate change with only mild disruptions of our current way of life. The biggest reason is the advance of technology. Renewable energy, energy storage, electric vehicles, and other green technologies have gotten so good, and so cheap, so quickly, that the economic incentives now favor decarbonization.

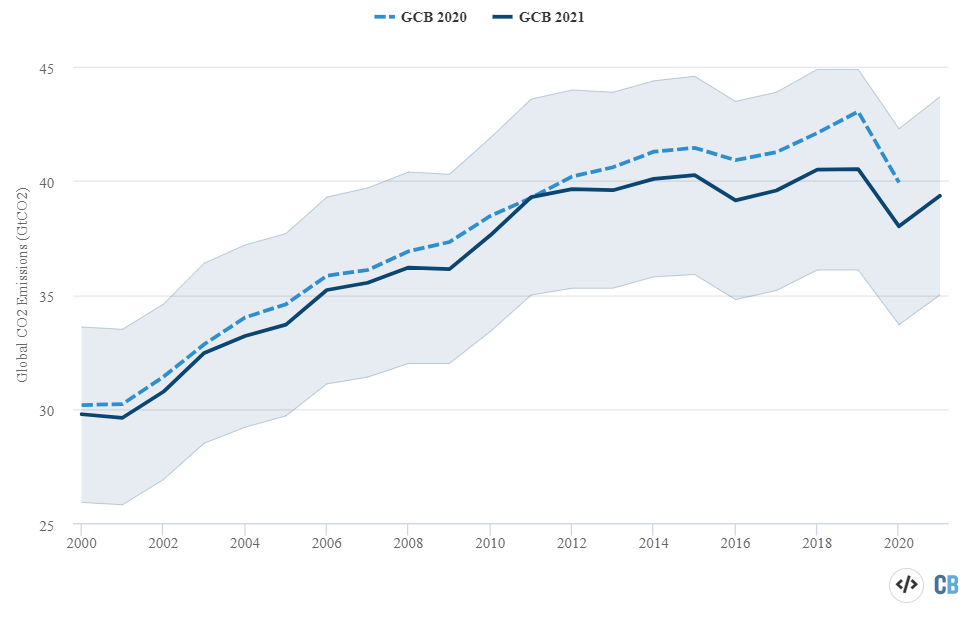

And this is not just theory. Recent data revisions from the Global Carbon Project show that total annual global carbon emissions — including from both fossil fuel use and land use changes — were approximately flat between 2011 and 2021:

Global annual emissions from electric power alone, meanwhile, peaked in 2018.

Now, annual emissions represent the total amount of carbon we add to the atmosphere each year, so the carbon in the air is still going up (and there’s also methane to think about). But the fact that a decade of rapid global economic growth wasn’t accompanied by any increase in global carbon emissions is a very good sign; as technology continues to improve, we should start to see big drops in annual emissions.

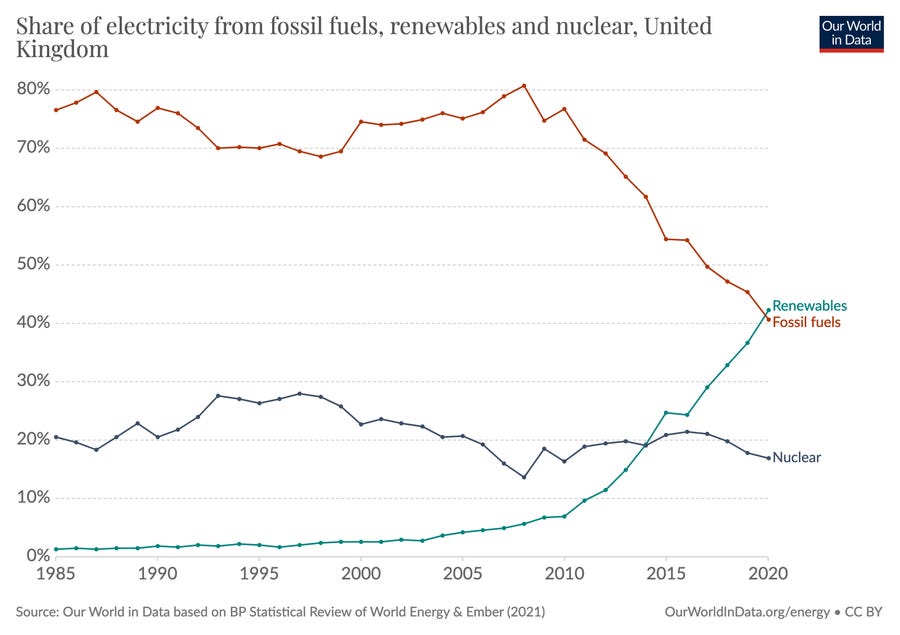

Now, technological improvement by itself is probably not enough to avert extreme outcomes from warming. But concerted government policy — by democratically elected governments in capitalist countries — can make a really big difference. The UK passed a climate change bill in 2008 that created a legally binding emissions target. As a result, the country began a rapid and sustained switch from fossil fuels to renewable power:

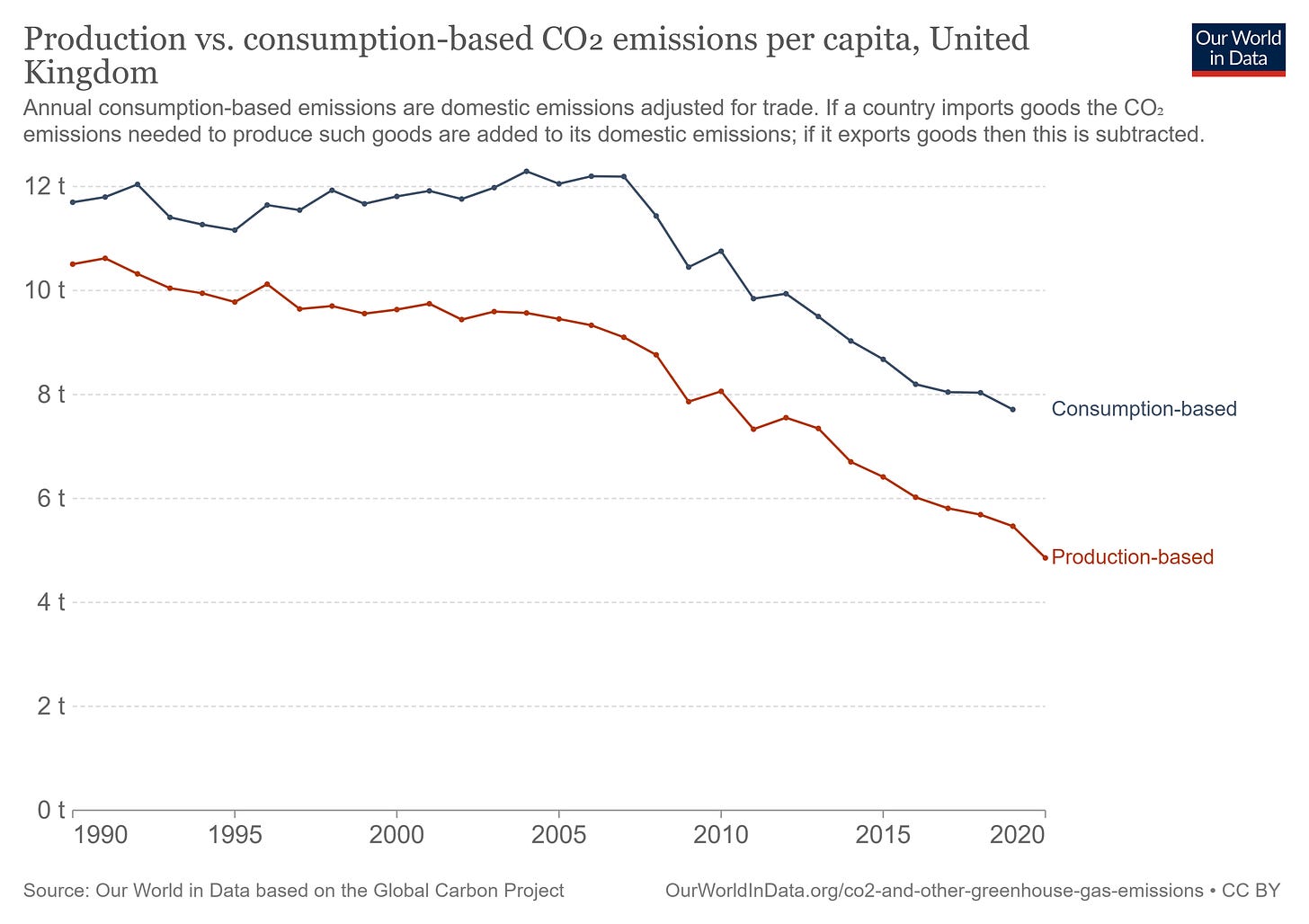

This resulted in a massive and ongoing decrease in the country’s total carbon emissions (yes, including when you adjust for trade and outsourcing):

The UK’s economy did suffer from the Great Recession during this time, but overall it grew (until Covid of course), all while reducing emissions drastically and switching to renewables rapidly. So it is possible to do this, and it doesn’t require degrowth, ecofascism, or any of the radical social transformations that online leftists assume we’d need.

Meanwhile, renewables are getting so cheap that even countries like China and India, who are loath to sacrifice even a tiny bit of economic growth for the sake of the global environment, are now making net-zero emissions pledges (China by 2060, India by 2070). These pledges aren’t binding yet, but the time frames fit very well with the scenario where we hold global warming to 2ºC.

So the window on climate change is narrowing. The rosy scenario has probably been missed, but the super-pessimistic scenarios are looking much less likely. In this thread, Ramez Naam looks at the recent data and concludes that the optimistic scenario is now 2ºC and the pessimistic scenario is probably 2.5ºC.

Now, that doesn’t mean everything’s fine and we can go back to sleep and muddle through with business as usual. These small-looking numbers conceal big differences — the effects of just 2ºC of warming are pretty dramatic, and 2.5ºC probably falls within the range of what we could reasonably label “global catastrophe”. So no matter what, Earth is in for a bumpy ride this century, and if we drop the ball on policy, some of the very dramatic scenarios could still manifest, technological progress or no.

But this doesn’t mean that climate change will force us to reorganize either society or our economy in radical or unprecedented ways. The UK’s experience shows that we can keep our social-democratic capitalist mixed economies and our modern democratic governments (or in China’s case, its modern autocratic government) and still do what’s necessary to avoid catastrophe by 2070 or so.

Stay mad, stay scared, stay hopeful

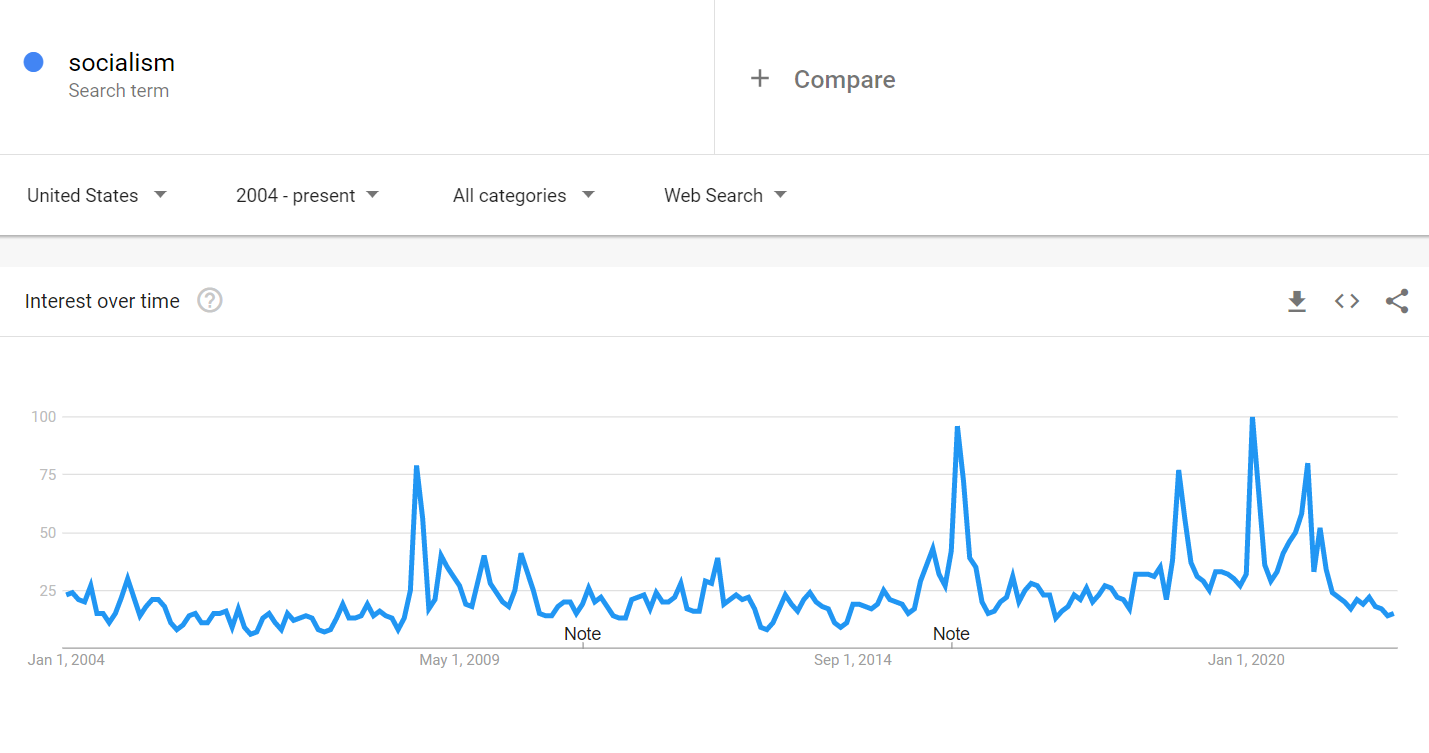

Anyway, back to the topic of our current unrest. Despite continuing eruptions of anger at school board meetings and such, I’ve seen some signs that unrest is peaking. Mass protests have largely died down, and — for better or worse — big policy changes in things like policing don’t look like they’re on the table. Meanwhile, public interest in alternative ideologies like socialism seems to be falling:

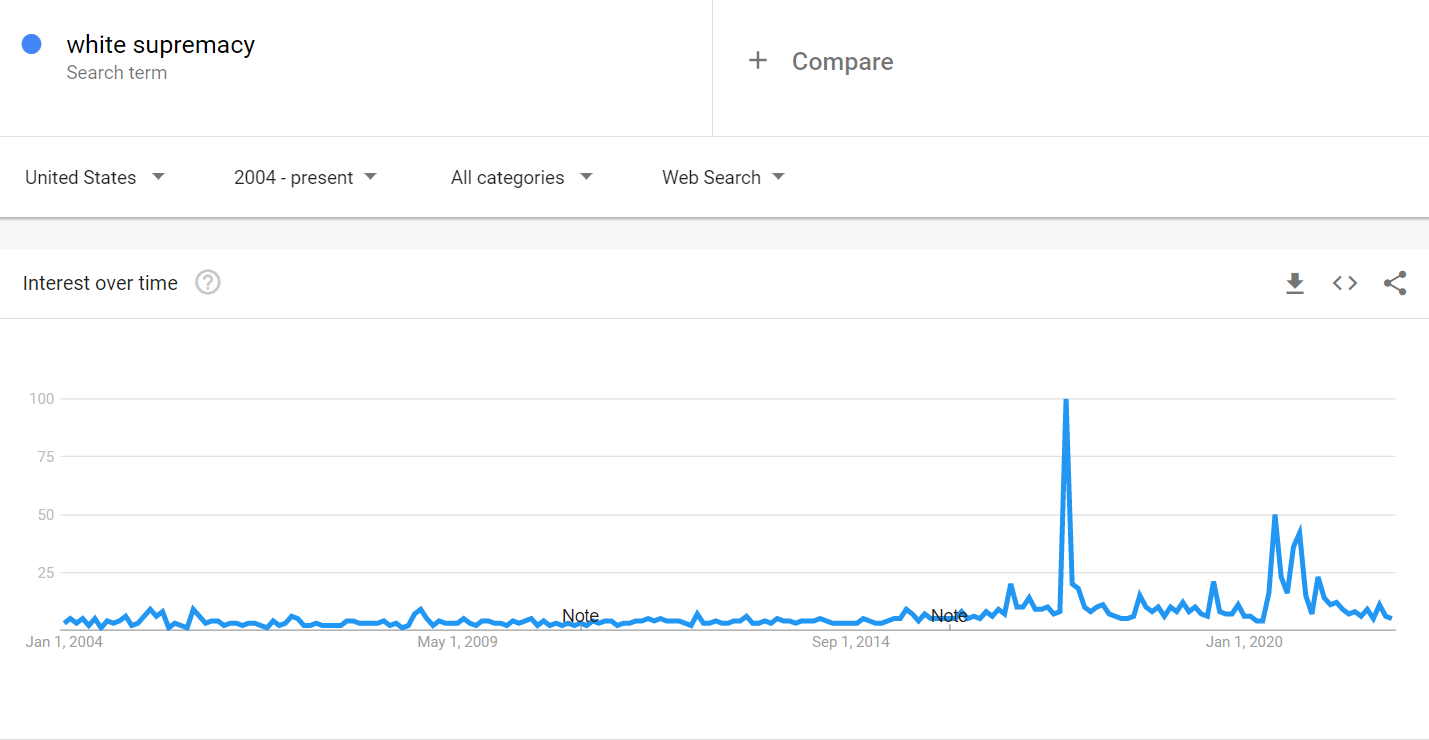

And searches for “white supremacy”, which peaked after Charlottesville and surged during the Floyd protests, are also down:

Various other search terms I tried, like “catastrophe”, also seem to be getting less common.

But that doesn’t mean the big fuss is over and we should all go back to sleep. First of all, as Peter Turchin’s theory of unrest stresses, the biggest factor suppressing unrest is when moderates believe that society will fragment unless they bestir themselves to restore order. In other words, we won’t go back to normal unless normal people stay scared and mad for a long time. Again, recall that Parable of the Sower was published in 1993.

And by the same token, it would be premature for us to abandon the impulse toward positive social transformation. The Climate Left may have no chance of ending capitalism, but they’ve inspired lots of center-left businesspeople, scientists, and policymakers to take climate change more seriously — which, ultimately, is what will contain climate change’s effects. And there are plenty of other problems in our society that will need big pushes in order to fix — our broken health care system, our ruinously high construction costs, and so on.

So while I want to reassure you, I only want to reassure you a little bit. America’s great strength is that we freak out about everything, thus bestirring ourselves to early action when other countries might have let problems fester too long. If all goes well, 20 years from now we’ll look back on the 2020s as when society started to become sane again and we started to rebuild after a decade of chaos and rage. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

“I have a message from another time.” — E.L.O.